When you come to Del Mar Racetrack, you will encounter thousands of people from every walk of life. Some arrive behind the wheel of luxury sports cars, sporting Rolex watches and linen suits. Others show up in flip-flops, t-shirts, and baseball caps, dressed for a lazy day at the beach. It’s a cross-section of California and beyond: old and young, rich and working-class, Black and White, regulars and first-timers. Some come to take in the sights and sounds, others come simply to be seen. That eclectic mix is part of what has made the seaside oval a beloved summer tradition for nearly a century.

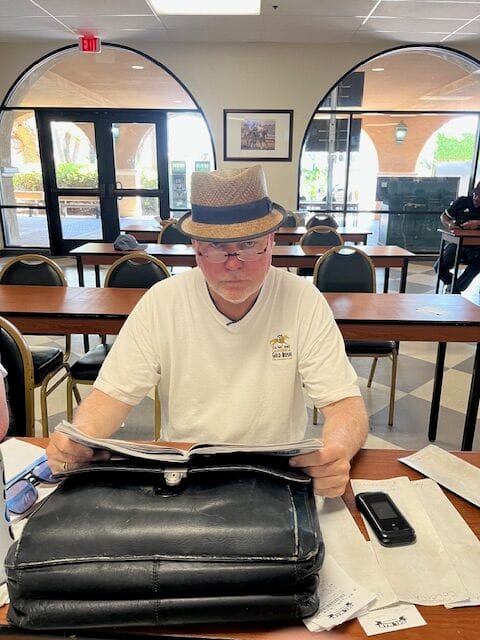

If you find yourself near the paddock, your eyes might come across a man who at first glance blends into the crowd. Dressed often in a sport coat, with glasses resting on his nose and a fedora tilted neatly atop his head, he watches the horses with quiet focus. You wouldn’t know it just by looking at him, but of all the stories gathered at Del Mar on any given afternoon, his might be the most remarkable and the hardest to believe. His given name is James Allard, but in the racing world he is affectionately known as Jimmy “The Hat.”

James Allard was born in April 1954 in Rochester, New York to a working-class family in the restaurant business. He comes from a self-described family of gamblers, but not of the horse-playing variety. His interest in horses was first spawned from his mother taking him to see a movie with horses in it and as Allard describes, it was game over for him after that.

While his family never made their name in the gambling business like Allard has, his family has a rich history in the restaurant business, which was a large part of his upbringing. His uncle, father, and mother all owned restaurants at one point, including famously his great uncle’s restaurant "Fred Allard’s" on State Street during Rochester’s heyday, when it was a booming industrial town filled with life.

However, his early childhood upbringing in Western New York was short lived when tragedy struck and his life was turned upside down when his father Everett James Allard, a decorated WWII veteran who spent nearly half a year in combat, died of a brain tumor shortly after the younger Allard’s fifth birthday. Allard’s mother remarried a man who due to his employment at the time, ended up being sent to Samsun, Turkey. Initially thinking it would not be a long stay, Allard's mother and stepfather left him behind in the States with family at first but soon realized that this would be an extended stay, so Allard, barely school age, traveled from Rochester, New York all the way to the Middle East by himself in the early 1960s. Not to be outdone by the absurdity of a young boy that age traveling halfway across the world on his own long before the introduction of cell phones, Allard laughs recalling all the funny looks he got from his fellow passengers when he decided to order a lobster of all things to keep his hunger satisfied on the long flights with stops in NYC, Frankfurt, Germany and Istanbul.

Allard went from waking up in one of the United States industrial hubs one day to waking up in a village he described as "100 years back in time" the next day.

His first morning in Turkey, he describes in detail waking up to the sound of bells and seeing a black carriage with red velvet interior steered by two perfectly matched Arabian horses. This was a prelude to just how different Allard’s life would be for the next three and a half years in Turkey. Despite barely speaking the language, Allard immediately began what he describes as his “hustle.” He started acting as an interpreter for the local Air Force base, getting the Air Force servicemen’s quota of blue jeans, and selling whiskey bottles on the black market.

In his spare time, he would ride the Arabian horses into the Black Sea and swim with them. Allard describes it as a real-life scene out of the movie Black Stallion.

After nearly four years in Turkey, Allard would return to the States and again settle in Rochester and soon his stepfather bought a motel and Allard returned to school. While Allard’s classmates and friends had progressed through grade school in the years he had been gone, Allard had spent nearly that entire time out of school living anything but a normal life. Allard soon had a nervous breakdown as he couldn’t adjust back to normal life in the States. To remedy this, his mother made an agreement with the young Allard in which she agreed to buy him a horse, as long as he continued going to school and kept up with his studies. That next year, Allard spent more time at Johnson’s Riding Stable, where his horse was located, than anywhere else. After the motel venture didn’t work out the family moved once again from Canandaigua, New York to Victor, New York, very closely located to Finger Lakes Racetrack in Farmington. While Allard had traveled to Batavia Downs as a younger child with his father, this would be his first true introduction to frequenting the track on his own. What started with one horse soon became several, and by the time Allard was 14 or 15 years old he started to hot walk horses for some of the barns at Finger Lakes. Allard who said he had also seen some horse racing in Turkey, credits that time outside the United States as giving him a great deal of perspective that he carries until this day. “My appreciation of how incredible this country we live in is because when you’re a kid and you see that kind of poverty, and you see people do things to people for a simple matter of survival, it gives you a whole different perspective.”

He also mentioned that’s part of why to this day he has as much, if not more respect for the bus boys at the racetrack than he does the billionaires.

All the while that all this is happening, Allard is progressing into his teens and spending more time getting acquainted at the track and less time at school and with his studies. Allard makes one more move back to Rochester with his mother and helps at night while she is operating a restaurant called the Sandwich Lovers shop. One night while Allard was cleaning and prepping for the next day, two gentlemen knocked on the door of the restaurant. This conversation which may have seemed insignificant at the time, would eventually help spawn what was the next chapter of Allard’s crazy story. One gentleman by the name of Peter Miller (not to be confused with the decorated racehorse trainer) accompanied by his brother knocked on the door of the restaurant. Despite being closed, Allard recognized the brother as a regular customer and opened the door. The brother familiar with the young Allard’s unique upbringing in Turkey and his experience at the track, prompted him to tell his brother Peter about all his interesting experiences. While telling his story about his adventures overseas, Allard inquired about what Miller did for a living. Miller told Allard he was an actor, on a show called Alias Smith and Jones (an early ‘70s Western series). After hearing about his experiences in show business, Allard decided right then and there, he was going to move to Hollywood and become a movie star. Allard went home and broke the news to his mother. His mother, sensing his seriousness, said at the very least he needed to graduate high school before going. Allard held up his end of the bargain and on September 1, 1974, he packed his bags and headed out West.

Allard was picked up by a cab at Los Angeles International Airport armed with $1,200 and a dream, when prompted by the cab driver “Where to?” Allard responded that he had no idea, but that he was there to be an actor and to take him to where the unemployed actors live. The cab driver ended up taking him to Brookside Country Club apartments at the corner of San Vicente and Houser. Allard walked in and by the time he got set up with his apartment and all the fees and paid the cab fare, he was down to around $300. Striking up a conversation with a gentleman on the street the following day, Allard was informed that there was a restaurant down the street that was a spot where actors in the area frequently found work. After catching the attention of the woman hiring that day, Allard began working at the Old World Restaurant at the corner of Beverly Drive and Wilshire. In a very fitting theme with the entire absurdity of Allard’s life up until this point, the very first customer to walk in on Allard’s first shift was none other than Hollywood legend Jon Voight. As if this wasn’t unbelievable enough, Allard mentions that Voight, who was a regular at the establishment, one day walked up to the register and asked Allard to hold his baby while he searched for something in his wallet. Little did Allard know at the time that child would go on to become an even bigger star than her father, that child’s name was Angelina Jolie. Allard acknowledges that many who hear his stories probably think he is making some of them up, and he doesn’t blame them. As he puts it, he doesn’t believe half of them himself.

While racing was never far from Allard’s heart or mind in his early days out West, he was determined to make his name in the movie business, and he did just that from the years 1979 to 1984. During that time Allard worked all kinds of roles on a staggering 500-plus shows. Some of his most prominent roles were as a regular guest on the TV show The Love Boat, where he appeared more than twenty times. He also played a police officer in the 1980 film The Blues Brothers and acted in Little House on the Prairie and The Rockford Files, among many others.

Allard, eventually tired of some aspects of the Hollywood business and after not getting the starring and co-starring roles he desired, decided to move on to what would be the next aspect of his life. Like much of Allard’s life, another seemingly chance encounter would lead to what would essentially become his life for a large part of the next decade. While hitting a heavy bag on Venice beach, he was approached and asked by a young man of similar age if he could jump in. That kid turned out to be famed kickboxer and multiple division world champion, Dennis Alexio. He and Alexio instantly hit it off and became best friends, Allard, who would eventually be the best man in Alexio’s wedding, worked as a sort of consultant and manager to Alexio’s career, traveling all over the world between Australia, Tahiti, France, Canada, and all over the United States. Allard, who describes this as a great time in his life, also acknowledges that this wasn’t a very lucrative opportunity financially and eventually exited this part of his life in the 1990s.

While Allard was still betting and going to the racetrack all the while pursuing his acting career and acting as a consultant for Alexio, things really took a turn in his horseplaying career when his friend Lenny Davidson took him to visit a company called Horse and Jockey, which was a horse information service that gave out information and picks for upcoming races. Allard, entirely unfamiliar with this aspect of the racing business, laughed to himself at the concept that there were three people sitting in an office full-time with people calling in with their credit card information, paying for information on horses. Still at the adamant behest of his friend Davidson, he gave it a shot. Allard describes his brief time at Horse and Jockey as not simply good but “stupid good.” In 1986, green at his new job he gave out a horse from Great Britain named Hawkley, who was 15-1 on the morning line but went off at 73-1 and paid $148.80 on a $2 win bet. The next morning when Allard showed up to work, he described a large line of customers who showed up with cakes and envelopes full of money ready to thank Allard. The owner quickly informed Allard that no one at the company had given out anything close to that.

This was just one of Allard’s picks that paid big over the years, but what really made Allard become a known name in handicapping circles and helped launch the legend of Jimmy “The Hat,” came on a January afternoon in the winter of 1989. Allard concocted a $3,840 Pick 9 ticket, along with a few other friends and horseplayers. One friend who was a prominent Los Angeles restaurateur, down on his luck and in the middle of a divorce and about to lose his restaurant, conceded to Allard minutes before the first post that he didn’t know what he was doing. This gentleman ended up handing Allard the funds to complete the Pick 9 ticket and the rest is history. Allard would go on to pick nine winners in a row and would win him and his partners a staggering $1,065,000 (the equivalent of $2.77 million today) and in that process also saved his friend’s restaurant. The final leg of the ticket was won by a horse named Naked Jaybird. Allard admits the only reason he included the horse was because of a close friend, a Kansas native who had passed away just weeks earlier. The last horse that friend ever bet on was Naked Jaybird, which inspired Allard to add the horse at the last minute.

After that race Allard and his associates were escorted up to the cash room and after-tax deductions were handed $848,000 in $100 bills. Allard owned 10% of the ticket, and himself walked out of the track with over $80,000. The talk of Allard’s big score was all over Los Angeles and the Southern California racing scene and from there the legend of Jimmy the Hat has only grown. Even the Jimmy “The Hat” moniker that has become his signature has some mystique to it. Multiple people claim to have given Allard that nickname over the years, but he gives credit to Ivan Puich, a jockey agent in the early ‘90s.

When further prompted for the background about when the gambling side of horses became a large facet of his life, he mentioned he was also reading the racing form at a very young age and has always had a great eye for horses. Not one much for technology, Allard relies in large part on his paddock profiling techniques. Allard, who does not own a computer and still carries a flip phone, relies on a keen eye sharpened by nearly three and a half decades of daily racing in Southern California, rather than the expansive technology many horseplayers use today. When asked what someone should look for before betting on a race, Allard explained the key factors he considers when examining a horse. Those details ultimately determine if, and how, he will place a bet at the window. Some of those facets he mentioned are looking at the horse’s overall condition, their coat, whether or not they are dappled out, the position of their ears, the gleam in their eye, if they have been given too much Lasix, what is their hydration level, any weight gain/loss. Allard reiterates while this is a very important piece of being a handicapper, it isn’t the end all be all, several other factors such as reading up on the racing form, watching race replays, networking with the people on the backside such as trainers, jockeys, and jockeys’ agents.

While not being a “technology person,” Allard may have more legitimate reason than most to be anti-technology. In 2002 with the Breeders’ Cup at Arlington Park outside of Chicago, a horse by the name of Volponi shocked the racing world when he won the Breeders’ Cup Classic, going off at 43-1 in an upset. According to Allard, he immediately sensed something was awry when he saw the winning tickets, claiming it was “fraud” and “impossible.” Eventually this became a lawsuit in which three individuals, including the mastermind of the scheme who was a programmer at Autotote (which handled roughly 65% of the North American horse racing handle at the time), ultimately ended up going to prison.

When further prompted about life as a horseplayer and how some people may say that they wished they could do that instead of having a “real job” and how much fun it must be. Allard sarcastically chuckles, “Try being stuck 30 or 40 grand for a month and going home with your stomach in a knot, trust me, it isn’t so much fun.” Being a horseplayer isn’t just about picking the horses; you must be able to ride the inevitable ebbs and flows that are bound to come in the life of a handicapper. Allard recalls being excited after hitting a Pick 6 for $72,000 only for it to be taken down by a rare jockey's objection, and ten minutes later, the ticket wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on. “You can be the best handicapper in the world but if you don’t have gambling courage and have the belief and confidence in your ability to be disciplined enough to wait for the best opportunities.”

Allard’s advice to new bettors is to keep it simple, Win, Place and Show, Exacta, Daily Double. He says that the exotic wagering menu has gotten too out of control and is turning new bettors off due to its complexity. That is part of Allard’s beef with the current state of the racing industry. When asked if he were made “commissioner” of racing what he would do, Allard said the people at the top must realize what business they are in. They are not in the entertainment industry; they are in the gambling industry and that’s what people come to the track to do is gamble. People love action and Allard mentions that that love of action helped build a little town in the desert by the name of Las Vegas and the various racetracks all around the country. He thinks somewhere along the line horse racing executives have lost sight of that and wants them to get back to that being the main focus, as that is what allows the machine to keep going.

Allard, now 71, shows no sign of slowing down. He carries the same fire and fascination for horse racing that he had as a kid watching races at Batavia Downs and Finger Lakes. In many ways, he’s the last of a dying breed, an old-school horseplayer who trusts instinct over algorithms, and hard-earned wisdom over anything a screen can tell him. His life has been anything but ordinary, filled with chapters that even he admits sound too wild to be true. What’s shared here only scratches the surface of the story behind the life of James Allard. And if that fedora perched atop his head could talk, you’d wonder why Hollywood hasn’t come calling already to tell his life story. There may never be another quite like Jimmy the Hat, and while that is sad to hear, maybe that’s exactly the way it’s supposed to be.